2016 Geome One Screening

Los Angeles, California

October 15, 2016

Sponsor: Threshold Stairs Media

A multimedia screening of Adi Da Samraj's Geome

One: Alberti's Window, in Los Angeles, Saturday, October

15, 2016. The outdoor event beautifully coincided with the full

moon.

Sections on this page:

Pictures

from the Screening Pictures

from the Screening

Click on images to view enlargements.

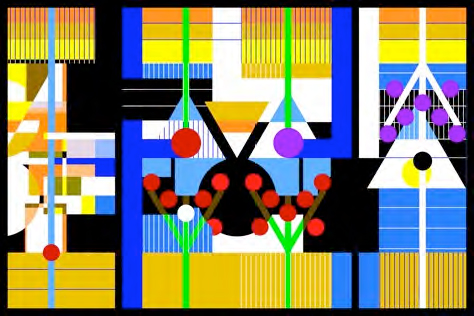

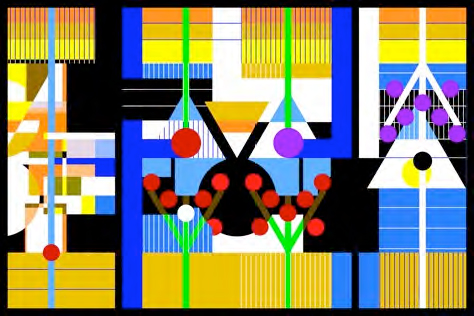

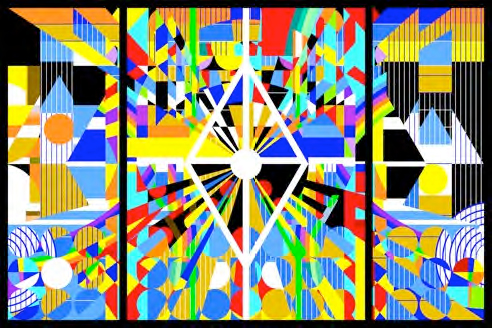

Albertiís Window I from the Geome One

Suite

(© 2016 ASA)

Albertiís Window I from the Geome One

Suite

(© 2016 ASA)

Albertiís Window I from the Geome One

Suite

(© 2016 ASA)

Albertiís Window I from the Geome One

Suite

(© 2016 ASA)

Albertiís Window I from the Geome One

Suite

(© 2016 ASA)

Albertiís Window I from the Geome One

Suite

(© 2016 ASA)

Albertiís Window I from the Geome One

Suite

(© 2016 ASA)

Albertiís Window I from the Geome One

Suite

(© 2016 ASA)

Albertiís Window I from the Geome One

Suite

(© 2016 ASA)

Albertiís Window I from the Geome One

Suite

(© 2016 ASA)

Adi

Daís Albertiís Window I Adi

Daís Albertiís Window I

Excerpt from Gary J. Coates' essay, The

Rebirth of Sacred Art: Reflections on the Aperspectival Geometric

Art of Adi Da Samraj.

Adi Da’s aperspectival art is radically different from

all forms of myth-based “God-art”, as well as

all forms of perspective-based “ego-art”, and

even all forms of non-perspectival and multi-perspectival

“ego-art” of the modern and post-modern eras.

He defines the images he makes as an entirely new kind of

artistic expression. “The image-art I make and do is

‘Reality-art’--not in the conventional sense of

image-art that imitates or merely reproduces ordinary ‘reality’…but

in the sense of image-art that intrinsically egolessly

coincides with Reality Itself.”41

The Last Supper, a perspectival fresco by Domenico

Ghirlandaio,

Cenacolo di Ognissanti, Florence, Italy. Photo: Nick Elias

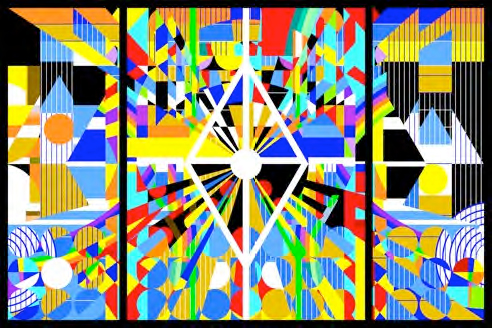

Center panel (Wednesday), Albertiís Window I, by Adi

Da Samraj

(with Vesica Piscis)

Albertiís Window I, by Adi Da Samraj (54 inches x 559

inches) invites the viewer release point of view based self-identity

and to fall into a world constituted by ďPrimary GeometryĒ

and ďPrimary ColorĒ that is free of the limiting, and ego-reinforcing

force of perspective.

By intention, then, both the design and experience of Adi

Da’s aperspectival images are radically different from

perspectival images such as Ghirlandaio’s fresco, a

fact which is powerfully evident in Alberti’s Window

I (2006-7), the largest (137 x 1,419 cm) example of Adi

Da’s recent geometric art to be included in the exhibition.

He explains: “I have given the title ‘Alberti’s

Window’ to the suite Geome One as a means of

pointing out that the image-art I make and do is, in fact,

not Alberti’s kind of space, not the traditional

space of Western art — which (first) 'objectifies' the

surface of the artwork, and (then) uses various devices to

draw the 'viewer' into the 'objectified' surface.”42

To fully understand and experience

this monumental work of art as intended, the viewer must first

un-learn his or her prior understandings of the nature and

purpose of art as well as his or her socially conditioned

habits of art viewing.43

At first glance, for example, one might be tempted to not

really “see” Alberti’s Window I,

preferring simply to breeze by it, casually noting how it

can be placed in its proper art historical category. Indeed,

it is possible to observe formal resemblances between this

image and similar works of a number of the masters of abstract

modern art. But to see this, or any other work by Adi Da Samraj,

merely as an exemplar of a type of art produced in the past

would be to miss the life-changing experience he intends his

viewer to have.44 Alberti’s

Window I, like all of the other image-art he has created

over a period of some forty years,45

is not merely a meaningless play of abstract forms and colors

on a two dimensional surface.46

Rather, it is a complex, paradoxical play between abstract

form and fundamental meaning intended to create a vehicle

for an ego-forgetting and ego-transcending aesthetic experience.47

Adi Da began the piece called

Alberti’s Window I by making photographs of

the environment in which he lives, including views looking

out of a window in his studio in Fiji. Using these images

“as a visual starting point — like a sketchbook,

and a key to unlock feeling memory”,48

he proceeded to make computer-generated images in response

to the image-content of his photographic “sketches”.49

By means of a spontaneous response to each iteration of the

developing image itself, he created over time an aperspectival

work of art radically different from the visual world of Ghirlandaio’s

fresco. Thus, as he explains, “The imagery in Alberti’s

Window does not follow the 'rules' of perspective, nor

does it presume the usual 'subject-object' orientation, as

if actually looking through a window to 'outside'. In Alberti’s

Window, the surface itself is the domain of the event

that is the image.”50

While meaning is maintained,

in part, by Adi Da’s constant reference to the original

photographs taken at the beginning of the process, the forms

and colors of Alberti’s Window I also embody

the fundamental principles of what Adi Da calls “Reality

Itself”, which, according to him, is what the world

is before it is perceived by any “point of view”

of any self-contracting ego-“I”. While it is clear

why and how linear perspective makes use of geometry to create

its spatio-temporal illusions, it is not so readily apparent

why or how Adi Da Samraj uses geometry to create order and

meaning in his art.

Noting with approval that Cezanne,

and various artists since Cezanne’s time, have created

art based on the use of primary geometries, Adi Da observes

that, when fully and deeply experienced, the structure of

human perception and the structure of the manifest world itself

are both rooted in the underlying presence and ceaseless play

of primary forces and geometries.51

He uses geometry as his primary means of artistic expression

in Alberti’s Window I, and his other aperspectival

geometric art, because he believes that this abstract formal

language speaks wordlessly and universally to the underlying

order of both self and world.52

Thus, because Alberti’s Window I is built out

of the interplay of primary geometries, it is possible to

tacitly feel, when standing in the presence of this monumental

work, that one is perceiving a meaningful field of generative

forces rather than a meaningless display of geometric forms.53

One experiences in the geometric structure of this work the

essence, rather than merely the outcome, of nature’s

processes of being and becoming.

But what of Adi Da’s use

of strong, radiant, and light-filled color in Alberti’s

Window I? Starting with his Spectra Suites in

2006, Adi Da has used a palette of “pure” colors

in order to orchestrate very specific effects: “A pure

color is a vibration…a piece of the spectrum of visible

light…Color is not arbitrary. It must be exactly right

for each image in particular. Color has emotional force.54

Colors in relation to one another generate, by that relatedness,

different modes, or tones, of emotional force.” He further

explains that, like primary geometry, color also “has

meaning in the nervous system, in the folds of the brain.

That meaning is not something that can altogether be stated

verbally, but meaning is inherent in color.”55

Thus, depending on the subject, each work of art he does requires

its own palette of colors.

Alberti’s Window I

is constructed out of a full spectrum of pure and vibrant

colors, which, like the crisp, precisely delineated geometries

characteristic of the piece, are made possible by the use

of digital technology and advanced methods of image fabrication.56

Color values range from light to dark, and include hues ranging

from cool tones at one end of the rainbow to warm ones at

the other. Each color strikes a different note, giving rise

to overtones and undertones of feeling-response and meaning-association.

One finds, for example, dark shades of cobalt blue as well

as airy tones of light-infused powder blue, in the cool end

of the spectrum, that evoke feeling-images of ocean depths

and endless skies. Robust, full-bodied hues of warm orange,

various shades of golden yellow and intense, otherworldly

reds trigger feeling-memories of spreading sunsets, the glowing

radiance of evening fires, and the rich earthy tones of soil

and rock. Woven amidst this complex field of geometrically

structured, multi-layered and interacting colors, one also

finds pure black and pure white.

Thus, even though one cannot

literally see painted images of the primal elements of earth,

air, fire and water, one can feel their presence. While Alberti’s

Window I is not representational, as in the case of such

“realistic” paintings as The Last Supper,

it does express at an archetypal level the all-pervading presence

of the primal elements and shaping forces which are always

at play in the constantly changing, self-regulating and dynamically

balanced natural world.

First panel, Albertiís Window I

Seventh and last panel, Albertiís Window I

Albertiís Window I

But, remarkable as this accomplishment might be for any abstract

geometric work of art, Adi Da, it will be remembered, claims

much more for his images than the mere depiction of the deep

structures and archetypal experiential qualities of cosmic

nature. “My image-art is made and done to perceptually

embody — and, thus, by means of the ‘aesthetic

experience’, to communicate — the inherently egoless,

non-separate, and indivisible Self-Nature, Self-Condition,

Self-State, and Perfectly Subjective 'Space' That Is

Reality Itself.”57

Such a bold intention would suppose,

at the very least, that the perceptible visual patterns, colors

and subtle qualities of images such as Alberti’s

Window I would be homologous to what he claims is the

very nature and structure of “Reality Itself”.

While words must always fail to describe that which cannot

be said, Adi Da does indicate that “Reality Itself”,

or “That Which Is Always Already the Case” has,

“no ‘thing’ in it, no ‘other’

in it, no separate ‘self’ in it, no ideas, no

constructs in mind or perception, and, altogether, no ‘point

of view’.”58

Does Adi Da’s art measure up to this standard? Does

Alberti’s Window I communicate a sense of non-separateness

and the “irreducible paradox of unobservability and

unknowability” that he claims is the “actual (Real)

state of every one and every thing — even in the apparent

context of all things arising.”59

When first gazing upon Alberti’s

Window I, the mind and the mind’s eye race to discover

the hidden order that structures and, therefore, explains

the power and beauty of the work. One wants to get a handle

on it, figure it out, domesticate its strangeness, reduce

its complexity to something simpler, something that can be

named and known. And at first, it seems that it might be possible

to do so. Yes, there are indeed organizing structures to be

observed. First of all, one notices that the great length

of the piece is divided into seven identically sized triptychs,

each of which has a larger central panel and two smaller side

panels. The central triptych, which has two large multi-colored

circles intersecting to create a large eye-like vesica

piscis, appears at first glance to give the work a kind

of overall symmetry. Yet, a closer look reveals that there

is, in fact, no overall symmetry: the images to the left of

the central triptych are more complex and less clearly ordered

than the panels on the right of it, which are calmer, less

brightly colored, more highly ordered and more figural. Thus,

while each individual triptych might remind one of the daily

movement of the sun from morning to night, the temporal rhythm

of the overall piece is directional as one moves from left

to right, rising to a peak of balanced harmony in the center

and falling back to a state of subdued calm and greater formal

simplicity at the end. One senses in this pattern the presence

of both circular time and linear time. With this insight,

the thinking, grasping mind has something else to say about

this enormous image, something else to hold on to.

Other formal ordering devices

also can be noted and described. There are, for example, both

horizontal and vertical regulating lines, which define fields

and sub-fields where changes in geometry and color tend to

occur. Certain form motifs repeat to give an overall sense

of unity: radial patterns originating in central white circles

dance across the length of the piece; fields of vertical stripes,

containing multiple figure-ground color reversals unify the

image in the vertical dimension; triangular forms and linear

arrow-like motifs keep showing up, creating a sense of rising

and falling forces; strongly colored red, yellow, white and

blue circles of various sizes emerge as recurring figural

forms, appearing at first to be clearly separate elements,

only later to be seen as circular windows opening views into

underlying, layered fields of color, which recede or advance

according to the laws of color perspective.

Second panel, Albertiís Window I

Sixth panel, Albertiís Window I

Albertiís Window I

The longer one spends with Alberti’s

Window I, however, the more it becomes evident that every

apparent ordering system is always also inevitably undermined.

Exceptions to the rule are the rule. Every instance of local

order arises only to dissolve again into a playfully creative

chaos, which is a paradoxical kind of order that can be felt

but never fully described. Eventually, one comes to the conclusion

that in Alberti’s Window I there is order without

system, in a work of art that is a living field of dynamically

balanced polarities. Symmetry and asymmetry, cool colors and

warm colors, horizontal lines and vertical lines, rising forces

and falling forces, circular forms and angular forms, advancing

colors and retreating colors, pure geometries and undefinable

shapes are woven together to create an image that is never

at rest, yet, always seems to be calm and centered. One slowly

comes to the understanding that in Alberti’s Window

I there are, indeed, no separate forms, and that a mysterious

sense of creative order and a prior, underlying unity are

all-pervading.

Finally, when the compulsive

search for order, purpose and meaning falls completely away,

and one simply becomes mindless in the face of the overwhelming

size, seductive beauty and incomprehensible complexity of

this monumental work of art, one discovers that Alberti’s

Window I cannot be defined or grasped by the mind’s

eye or the ego’s “I”. The only possible

response that is left is to surrender, simply and spontaneously

to the allure of the piece and to wander happily without any

“point of view” in the dimensionless spaces of

this primal landscape, which is a reality that is both familiar

and strange. Forms are then felt with the “eyes of the

skin”,60 colors

are sensed as temperatures and qualities of being, and order

is experienced as what Adi Da describes as a “non-necessary”

and “non-binding” appearance arising out of an

unseen reality both infinite and filled with light. In this

realm and state, there is no time and there is no space. This

experience brings a sense of freedom that is unthreatened

and unthreatening. There is only pleasure and delight that

spontaneously and naturally arises as soon as the frenzy of

seeking and the need to name and control is forgotten. This

is the experience that Adi Da describes as “aesthetic

ecstasy”, which is his true purpose in creating his

art:

|

The living body inherently wants to Realize (or Be

One With) the Matrix of life. The living body

always wants (with wanting need) to allow the Light

of Perfect Reality into the “room”.

Assisting human beings to fulfill that impulse is

what I would do by every act of image-art. My images

are created to be a means for any and every perceiving,

feeling, and fully participating viewer to “Locate”

Fundamental and Really Perfect Light — the world

As Light, conditional (or naturally perceived)

light As Absolute Light. Ultimately, when "point

of view" is transcended, there is no longer any

"room" or (any separate "location"

and separate "self") at all — but only

Love- Bliss-"Brightness", limitlessly

felt, in vast unpatterned Joy.61

|

Third panel, Albertiís Window I

Fifth panel, Albertiís Window I

Albertiís Window I

Wassily Kandinsky wrote in 1910-11

that, “The great epoch of the Spiritual which is already

beginning…provides and will provide the soil in which

a kind of monumental work of art must come to fruition.”62

Were he alive today, Kandinsky might well consider the monumental

art of Adi Da Samraj to be the fulfillment of the spiritual-artistic

impulse that he and other revolutionary artists at the beginning

of the twentieth century sought to bring into the world through

the invention of abstract art. If properly understood and

rightly and fully experienced, the aperspectival geometric

art of Adi Da Samraj can be seen as a harbinger of a new age

of consciousness and culture.

|

|

|

ďI Am Manifesting the self-organizing force of Reality

in the context of perception and communicationóand,

therefore, of images.Ē

Adi Da Samraj

|

Notes Notes

41

Adi Da’s “Reality-art” must be understood

as the result of a “profound philosophical and Spiritual

preparation.” He says that only after decades of the

most intensive consideration was he able to discover “the

means to go through and beyond all traditional and ego-based

modes of thinking and understanding”, making it possible

to finally make images “on an intrinsically and entirely

“point-of-view”-less basis.” As quoted in

Adi Da Samraj, Perfect

Abstraction, pg 16

42

Adi Da Samraj, Aesthetic

Ecstasy, pg 31.

43

As Adi Da says, “My image-art can be characterized as

a paradoxical space that undermines “point of view”.

That undermining (which occurs in any instant of fully felt

participation in any of the images I make and show) allows

for a tacit glimpse, or intuitive sense, of the Transcendental

Condition of Reality (even as all conditional appearances,

and, Ultimately As It Is) — always, inherently, and

totally beyond and prior to ‘point of view’.”

Adi Da Samraj, Transcendental

Realism: The Image-Art of egoless Coincidence With Reality

Itself, op. cit., pg 53.

44

“By viewing Alberti’s Window I in this art-historical

manner, I, along with even all artists who make and do images

in the geometric abstractionist mode, am eased into a convenient

position in the historical sequence of academically defined

space and time. Such a manner of viewing image-art is, ultimately,

a choice to ‘objectify’, control and be indifferent

toward the perceptually-based opportunity of profundity that

image-art is”. Adi Da Samraj, Aesthetic

Ecstasy, op. cit., , pp 14-15.

45

Adi Da argues that even though his art is abstract, meaning

is intrinsic to it: indeed, he claims that each of his works

produced over a period of more than forty years, from his

Zen-like brush paintings and multiple exposure photography

to his more recent computer-generated imagery, expresses a

fundamental tension between abstract form and meaning. For

an excellent survey of Adi Da’s entire artistic production

to date, see Mei-Ling Israel, The

World As Light: An Introduction to the Art of Adi Da Samraj,

Middletown, CA, The Dawn Horse Press, 2007. For an explanation

of the relationship between form and meaning in his work see

Adi Da Samraj, Transcendental

Realism: The Image-Art of egoless Coincidence With Reality

Itself, op. cit., pg 55.

46

He explains that he makes art that “embodies a disposition

that transcends both the ‘new’ view of image-art

as ‘surface only’ and the ‘old’ view…of

the image as a perspectivally-organized ‘window on the

world’.” See Adi Da Samraj, Aesthetic

Ecstasy, pg 14.

47

Adi Da Samraj, Transcendental

Realism: The Image-Art of egoless Coincidence With Reality

Itself, op. cit., pg 55.

48

Adi Da Samraj, Aesthetic

Ecstasy, op. cit., pg 32.

49

As is the case with all his digitally fashioned art, Adi Da

was assisted by a team of computer technicians staffing multiple

computers. He gives precise instructions about what he wants

done in terms of the form and color of the image until he

feels that the work is completely resolved. In this way of

working, nothing stands in the way of his ability to be completely

immersed in the spontaneous process of image development.

50

Adi Da Samraj, Aesthetic

Ecstasy, op. cit., pg 32.

51

Based on his own direct meditative experience Adi Da reports

that “if the deep process whereby the brain makes perception

happen is profoundly felt and (thus) understood, then it can

also be understood that the basis of the natural world’s

construction as perceptual experience is primary geometry,

or elemental shape — curved, linear, and angular.”

Not only is the perceptual process so structured, but he also

observes that “The natural world itself is (inherently)

a self-morphing and self-limiting construction (or a naturally

improvised and spontaneously self-organizing art-form), formalized

and fabricated by means of a plastic interaction between primary

forces and structures… Everything perceived is a structure

that demonstrates the interaction of these three all-patterning

forces of shape”. See Adi Da Samraj, Transcendental

Realism: The Image-Art of egoless Coincidence With Reality

Itself, pp 55-56.

52

The reason we don’t normally perceive that this is the

case, Adi Da explains, is because of the inconceivable complexity

of the interactions of primary geometries characteristic of

the natural, material world, which create an appearance of

rounded softness when seen by the natural eye. (see The

World As Light, op. cit. pg 99, and Transcendental

Realism: The Image-Art of egoless Coincidence With Reality

Itself, pg 56) Adi Da states, however, that even if

it is not possible directly to perceive the fecund and generative

presence of primary geometries in nature, “it is altogether

possible to tacitly feel that whatever is actually being perceived

in any moment is something structured in the primary geometric

manner, and that (consequently) all apparent complexity is

based on very simple primary elements.” As quoted in

Transcendental

Realism: The Image-Art of egoless Coincidence With Reality

Itself, op. cit., pg 56.

53

In an essay called “My Working Principles of Image-Art”,

in his book Transcendental

Realism: The Image-Art of egoless Coincidence With Reality

Itself, Adi Da summarizes twelve ways by which meaning

in his art is constituted through abstract geometrical form.

Several are worth quoting in order to clarify assertions made

in the main text of this essay. “5. The image-whole

is meaningful form; 6. Meaningful Form is always a play upon

the intrinsic aesthetic laws of pattern that are inherent

to the human brain and nervous system, and that underlie all

aspects of human perception, cognition , and action; 8. The

formal characteristics of the image-totality are a play between

two modes of motion (or of patterning tendency) — the

motions that are tending toward symmetry and the motions that

are tending toward asymmetry; 9. The finally realized image-whole

is a balanced resolution of the inherent conflict between

symmetry and asymmetry…; 10. Within the formal (or

meaningfully formalizing) elements of the image-play are characteristics

of polar opposition in mutual dynamic association…;

11. The finally realized image-whole is, necessarily a unified

whole, a perceptual order that is characterized by an equanimity

that demonstrates a realized balance of and between (or in

the context of) all the opposites within the meaning-field

and the image-plane; 12. The finally realized image-whole

is, necessarily, a perceptual demonstration of (both) the

root-principle of the prior unity of all conditionality and

the Transcendental Principle of the Primal Equanimity of Reality

Itself…” pp 45-46.

54

Mei-Ling Israel, The

World As Light, op. cit., pg 96.

55

Adi Da Samraj, as quoted in The

World As Light, ibid., pg 96.

56

Adi Da Samraj, ibid., pg 95.

57

Adi Da Samraj, Aesthetic

Ecstasy, pg 39.

58

Adi Da Samraj, Transcendental

Realism: The Image-Art of egoless Coincidence With Reality

Itself, op. cit., pp 56, 57.

59

Adi Da Samraj, ibid., pp 56-57.

60

For an insightful and inspiring essay on the negative effects

of the dominance of the visual sense in contemporary architecture

and culture, and the need to create an environment that speaks

to all the senses see, Juhani Pallasmaa, The

Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses, Wiley-Academy,

2005.

61

Adi Da Samraj, Transcendental

Realism: The Image-Art of egoless Coincidence With Reality

Itself, op. cit., pg 57.

62

As quoted in Maurice Tuchman (ed.), The

Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985, New

York, New York: Abbeville Press, Publishers, 1986, pg 11.

|